Tagged Tiger Shark ‘Quinty’ swims from the Saba Bank to Trinidad in four weeks!

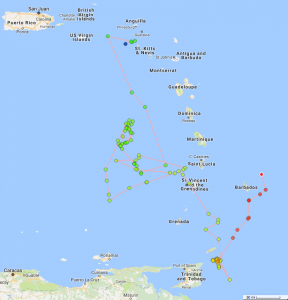

During the Save Our Sharks expedition last year, a number of tiger sharks were caught on the Saba Bank and fitted with satellite tags to study how these animals move around the Caribbean Sea. This research provides invaluable information about shark migration and it is the first time that work of this kind has been carried out in Dutch waters. The sharks were tagged as part of the region-wide Dutch Caribbean Nature Alliance “Save Our Sharks” project which is funded by the Dutch National Postcode Lottery. The first tiger shark to be tagged with a satellite transmitter was named “Quinty”, after Quinty Trustfull, television personality and Dutch Postcode Lottery ambassador. Now Quinty’s travels can be tracked live by visiting the following site

Trinidad is the center for the trade in shark fins and meat in the Caribbean. It is ranked the number six country in the world that exports shark fins to Hong Kong – the world’s largest shark fin market. In 2011 Trinidad and Tobago exported as much as 332,396 kg of shark fins to the Asian market. As if spending time in Trinidadian waters was not dangerous enough, swimming from island to island can be a perilous undertaking for a shark. Of the 52 nation states in the Caribbean only three have so far established shark sanctuaries and have the necessary protection in place to protect these important apex predators: the British Virgin Islands, Bonaire – Saba and St Maarten. Whether she realized it or not, Quinty took her life in her hands as she traveled through ten different territorial waters in the Caribbean where she could have been legally caught and killed for her fins, meat, oil or cartilage, joining over 100 million sharks which are killed annually worldwide to feed the trade in shark fins which are considered a delicacy in the east.

Quinty’s journey highlights the fact that we are not doing nearly enough to protect these thrilling animals, which are essential to the health of our oceans and our endangered coral reefs. Regional-wide protection for sharks is needed now more than ever. “We are thrilled that to be able to conduct this research, especially since it is unprecedented in this area,” commented Tadzio Bervoets, Project Manager of the Save Our Sharks project. “When looking at the long migration that Quinty is making, one realizes that local protection of sharks is insufficient, and shark conservation should be prioritized on a regional scale.”

During the Save Our Sharks Expedition 2016, four tiger sharks were tagged in Sint Maarten and on the Saba Bank with satellite tags, allowing scientists and conservationists from the Saba Conservation Foundation, the Sint Maarten Nature Foundation and the Shark Education and Outreach Organization Sharks4Kids to track the animals and to gather information about their migration patterns. The tags were attached to the dorsal fin of the tiger sharks. Each time the dorsal fin breaks the surface, its location is sent to the satellite. Visitors to the Save Our Sharks website can follow the current swimming route of one the tagged tiger sharks, Quinty, has made since October.

Tiger sharks are one of the largest species of shark. They can grow up to 4,5 meters long and live for up to 50 years. They are one of the oceans’ most powerful predators and are known to migrate vast distances in search for food, a mate or breeding grounds. Their diet includes everything from jellyfish to stingrays and seals. Tiger sharks are so regularly sighted on the Saba Bank that they have been adopted as the Saba Bank ‘mascot’. Unfortunately, they are classified on the IUCN Red List as “Near Threatened”.

Little is currently known about the status of shark populations in Dutch and regional Caribbean waters and tagging studies are a pivotal first step in determining which sharks are present, where they can be found and most importantly how best to improve regional management and protection of these important apex predators.